The Super Bowl tells us so.

The Super Bowl Indicator

The championship of American football decides the direction of the US stock market for the year. If a “National” team wins, the market goes up; if an “American” team wins, the market goes down. Yesterday the Giants, a National team, beat the Patriots.

The birth of the indicator was quite auspicious.

Eight years ago I wrote about using random permutation tests to explore the efficacy of the indicator. One of the points is that the fraction of correct predictions is not necessarily a good indication of the value of a predictor.

Thanks to Robin Blumenthal of Barron’s we now have updated data. The indicator has been right 28 times out of 45. Now I should say at this point that over the years the notion of “National” versus “American” has become fuzzy. Also people have tried to fudge the meaning of “market” to make the indicator look better (the Dow Jones Industrials is used here). So other values of “number correct” are possible.

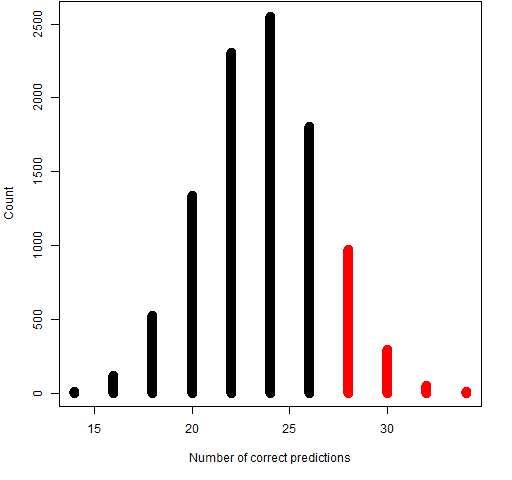

Figure 1 shows the results of a permutation test on the 45 years. The p-value for this test is about 13%. Only 3 of the 8 updated years were correct.

Figure 1: Random permutation test of 45 years of the Super Bowl Indicator.

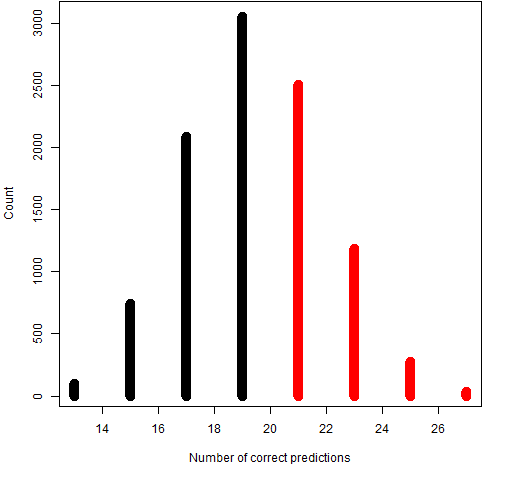

This, of course, includes the years that were used to form the “hypothesis”. A stricter test excludes the first 11 years. Figure 2 shows the permutation test in this case. The p-value here is about 40%.

Figure 2: Random permutation test of the Super Bowl Indicator excluding the first 11 years.

The meaning of p-values

What does a p-value of 13% or 40% mean?

The setup

Statistical hypothesis tests start by assuming a “null hypothesis” is true. Calculations are performed as if this hypothesis were true. The p-value is the probability of seeing something at least as extreme as the actual result under those calculations.

The permutation tests done for the Super Bowl have the null hypothesis:

- the Super Bowl does not predict the market

If it doesn’t predict the market, then it doesn’t matter which team wins. The test shuffles the winners and counts the number of correct predictions. That is done a large number of times (10,000 in this case).

Figure 1 shows that there were a few permutations that resulted in 34 correct predictions, and also a few that resulted in 16 correct predictions. There were no cases more extreme than these.

If the p-value is small enough, we reject the null hypothesis.

The common misinterpretation

Undoubtedly the most common error in interpreting p-values is to think:

The p-value is the probability that the null hypothesis is true.

That is written in red because it is absolutely positively definitely WRONG.

By my reckoning the probability that the Super Bowl does not predict the market is 100% (to rounding error) — not 13% or 40%.

Surprise

P-values are about surprise, not believability.

When you do a hypothesis test, you are playing a game — like a lottery. But this is sort of a reverse lottery. You know you have “won”, the p-value tells you how surprised you should be that you won.

In the Super Bowl test we got a p-value of 13%. Not much surprise.

In “The distribution of financial returns made simple” there is a test of the null hypothesis that the daily log returns of the S&P 500 are normally distributed. The p-value for that test is 10 to the minus 2762. If we have a one in ten million chance of winning a certain lottery that we play once a week, then this p-value is equivalent to winning that lottery every week for seven and a half years. I think we are surprised.

Hypothesis believability

How much we should believe a hypothesis depends on more than p-values.

Here are my beliefs about the two null hypotheses:

- Super Bowl does not predict market: believe

- Normally distributed returns: do not believe

In both cases my beliefs are at the absolutely-positively-definitely level. But my beliefs are arrived at differently in the two cases.

The null hypothesis for the Super Bowl is inherently very believable to me. Plus we don’t get a very surprising p-value. It would take an extremely surprising p-value to overcome my inherent belief because I see no plausible mechanism that would make a sports game affect the stock market.

The null hypothesis of normally distributed returns is also inherently believable — it is reasonable to expect that. However, we get an extremely surprising p-value. This outweighs the inherent belief. It takes essentially absolute faith in the inherent believability — as the persona of the return distribution post has — in order to ignore the surprise of the p-value and hold to the null hypothesis.

Financial addendum

Above I said:

I see no plausible mechanism that would make a sports game affect the stock market.

I lied. (See the epilogue of this.)

If the statement had been about some physical system, that would have been fine. But this is finance and there is a plausible mechanism — if enough people believe it, it can become true. In finance there can be self-fulfilling models.

Parental logic — it’s true because I say it’s true — is hard for children to deal with. It is hard for adults as well.

Epilogue

And they asked if I believe

And do the angels really grieve

from “I Am the Ride” by Chris Smithers

Appendix R

get data

The main data can be put into R with the command:

dowjones.super = read.table("https://www.portfolioprobe.com/R/blog/dowjones_super.csv", header=TRUE, sep=",")

With or without R, the file is at https://www.portfolioprobe.com/R/blog/dowjones_super.csv

The functions (plus the superscore object) are in permutationTest.R. You can get these into R with:

source("https://www.portfolioprobe.com/R/blog/permutationTest.R")

There are some subtle changes in the plot function compared to the one released with the “Permuting Super Bowl Theory” paper.

compute the tests

fulltest <- permutation.test.discrete(dowjones.super[,"Winner"], dowjones.super[,"DowJonesUpDown"], superscore)

latetest <- permutation.test.discrete(dowjones.super[-1:-11,"Winner"], dowjones.super[-1:-11,"DowJonesUpDown"], superscore)

plot the tests

plot(latetest)

plot(fulltest)

Pingback: A look at Bayesian statistics | Portfolio Probe | Generate random portfolios. Fund management software by Burns Statistics

I have R version 3.0.2 (2013-09-25) — “Frisbee Sailing” installed.

In attempting to run the R code appendixed to The Super

Bowl Indicator, ‘Random.seed’ object not found error occurs when compute the test code lines are pasted in. I would be grateful if you could advise how I can correct this error.

Many thanks J Wright

Great problem — thanks for sharing.

“Great” because it seems like it would be impossible to get this message — if ‘.Random.seed’ doesn’t exist and it is needed for a random calculation, then R automatically creates it.

What is happening here is that the permutation test function wants to save the random seed and it doesn’t check to see that it exists.

A workaround is to do a command that forces the random seed to be created if you get this error. For instance:

runif(1)

A better implementation would check to see that the seed exists before saving it, and do the forcing trick if it doesn’t.

Many thanks Pat. The runif(1) workaround

works wonderfully. The R support community must be one of the main reasons

that R continues to gain in popularity.

J Wright